News - United States of America

Looking up into a personal path of discovery

NH students collect data for NASA studies of 2017 eclipse

August 21, 2017, the day the sun and the moon shadow danced across the United States, brought a multitude of memories…and gifts. For astrophysicists, biologists, meteorologists, entomologists—almost any science “ists” you can name—the eclipse rendered literally billions of data that will deepen our understanding of the universe, from the elements found in faraway stars to the behavior of Earth-bound microorganisms.

For those who wanted only to see an eclipse in their lifetime, the rewards were perhaps less quantifiable but just as profound: awe, astonishment, contemplation, celebration, and maybe even a few moments of shared, absolute silence.

But while the sight of the moon drifting across the face of the sun was stunning, it was the image of millions of faces looking up – not down at our smart phones, not down at our laptops, not down at our feet lost in thought – but up at a natural miracle that made this eclipse different from any that have come before.

GLOBE Program US Country Coordinator Jen Bourgeault, who is based at the Joan and James Leitzel Center for Mathematics, Science, and Engineering at the University of New Hampshire, noted that any of her UNH peers with a professional interest in the eclipse was far from campus that day, conducting experiments in or near the path of totality.

But Jen, who lives and breathes for opportunities to connect young learners with authentic science work, was committed to making the day memorable and meaningful to students close to home.

Working with the staff at Coe Brown Northwood Academy, a high school in southern New Hampshire, Jen and a small team of volunteers—armed with the GLOBE Observer app designed by NASA—set up stations at the school to take temperature readings and recruit students to help them in the data collection.

Of course, science can be messy, and it just so happened that the eclipse happened on the first day of school at Coe Brown (always a time of controlled chaos) and during the hour when students were streaming out the doors to catch their buses home.

So Jen and her volunteer team—Sarah Widlansky and Kiley Remiszewski (both Ph.D. students in UNH’s Natural Resources and Earth Systems Science program), Susan Cox of the U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Alicia Carlson from UNH Cooperative Extension, and second grade teacher Erin Hollingsworth of Gilmanton Elementary School—jumped right into the crowds, inviting students to be part of something historic by taking and recording air and ground temperature readings.

Of course, some resisted: “I don’t know, I feel like a goof just looking up at the sun,” said one young man.

But for others, the selling point was the chance to feed information directly into NASA databases and to collect information that would become a part of scientific discovery.

Said one smiling freshman, “Sure, I guess it would be cool to tell my grandchildren that I contributed to a NASA experiment.”

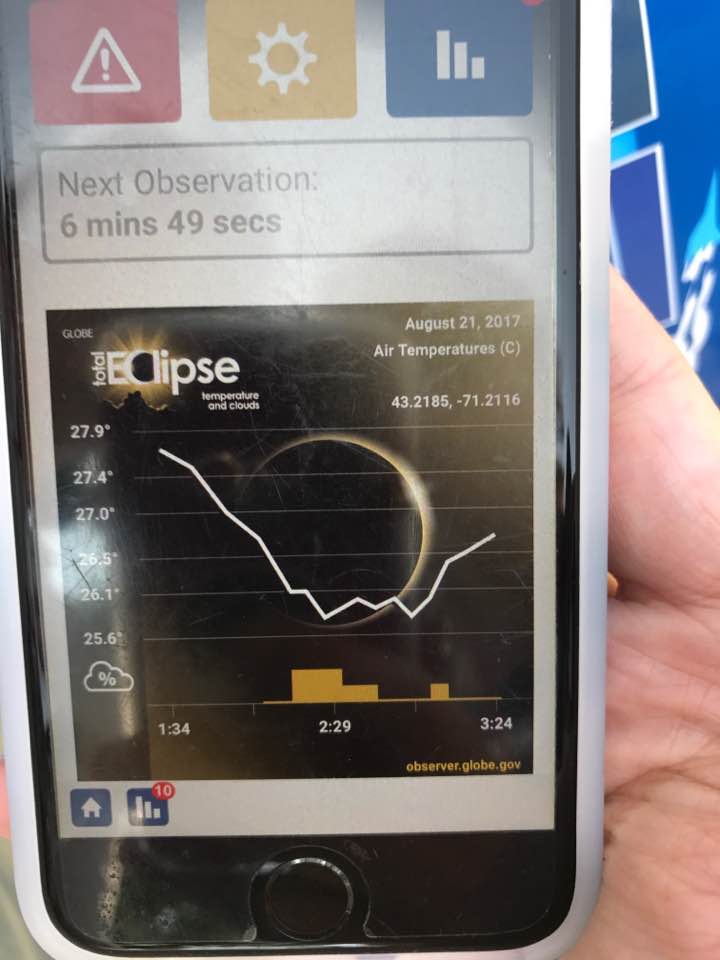

The task of entering data into the GLOBE app was both straightforward and challenging (and, yes, required looking at smart phone screens, but strictly in the name of science). Three thermometers (Centigrade) were suspended from branches in full shade under three different trees. Every ten minutes, beginning one hour before totality (about 62% in southern New Hampshire) and ending one hour after totality, the volunteers took an air temperature reading and entered it in the app.

At the same time, another student would point a device somewhat like a traffic radar gun at three different spots on a grassy or paved surface to take infrared readings.

The challenging part—and the aspect of data collection that generated the most discussion among students—was describing the type(s) of clouds and how much of the sky had cloud cover at each moment of data collection. Using a sheet with photos of cloud types, the students had to make their best guesses about what was happening in the sky when they took their readings.

On a day that was generally brilliantly sunlit, there was still a lot of cloud movement and variation to assess as important variables: were recorded changes in temperature, even by a single degree, caused by cloud cover or by the moon drawing its curtain across the sun? (One observation made by several students: when looking at the eclipse through safety glasses, clouds appear as eerie dark mists, as if drifting through moonlit horror movie.)

By tracking the entered data in real time, the GLOBE app created a graph showing spikes and dips in air temperature. Students crowded around to watch the graph track the changes, excited to “see” their data but knowing that single data points can be anomalies, or temperature dips caused by cloud cover. It will be the analysis of, literally, billions of temperature readings taken across the swath of the eclipse that will reveal accurate trends.

While the GLOBE team did its work, clusters of other Coe Brown students and their teachers were busy with their own eclipse activities, catching as many minutes as they could before the buses left for home.

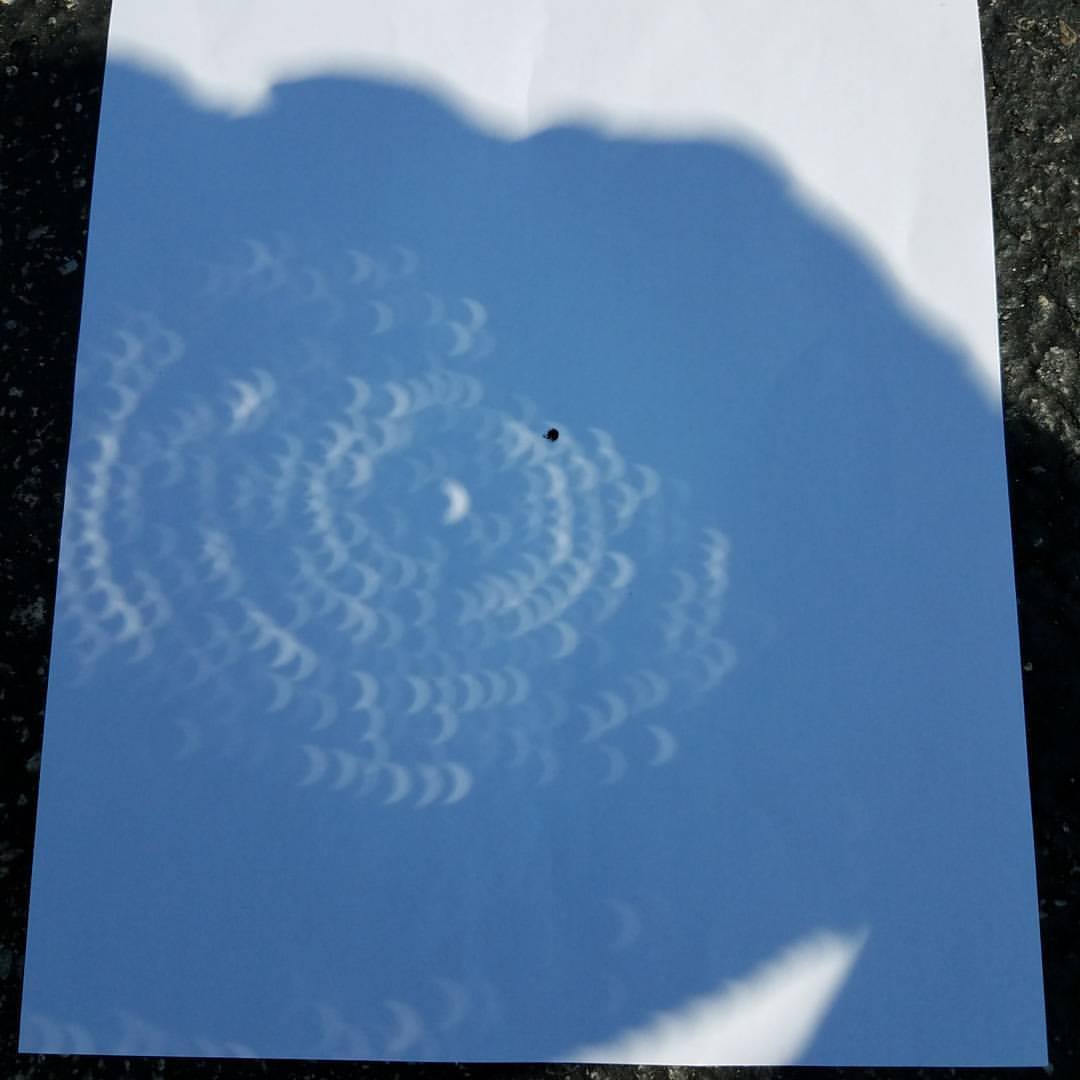

Engineering teacher Scott Goelzer used a variety of lenses to bring a small image of the eclipse into focus on a piece of white paper. (He also demonstrated how a lens focusing the light of the sun could cause intense heat, inviting a fellow teacher to put out his hand to see just how hot it could get.) It’s worth noting Goelzer was feeling some envy on eclipse day: his daughter was on a mountaintop in Idaho directly in the path of totality.

One of Goelzer’s students offered the use of the binoculars in her parent’s car to see if the same principle would work, and it did—creating side-by-side eclipses about the size of a dime. And, of course, some groups were using the low-tech, tried-and-true method of a cardboard viewing box with a pinhole on one side to reveal the almost perfectly round sun/moon discs overlapping, like a magician in the midst of making a coin disappear.

But perhaps the spur-of-the-moment experiment that drew the most “wows” happened when Susan Cox realized that her wicker sunhat had many round-ish holes, and inspiration struck. She put a piece of white paper on the ground, took off her hat and held it about four feet from the paper, moving it back and forth (like focusing a lens) until, with the sun shining through one of the holes, a perfect image of the eclipse came into focus on the ground. The GLOBE team, students, and teachers cheered at her ingenuity and discovery.

But perhaps the spur-of-the-moment experiment that drew the most “wows” happened when Susan Cox realized that her wicker sunhat had many round-ish holes, and inspiration struck. She put a piece of white paper on the ground, took off her hat and held it about four feet from the paper, moving it back and forth (like focusing a lens) until, with the sun shining through one of the holes, a perfect image of the eclipse came into focus on the ground. The GLOBE team, students, and teachers cheered at her ingenuity and discovery.

And as for the young man who at first refused to look at the eclipse because he felt goofy? His girlfriend eventually put on the safety glasses and looked up. For a moment, she was breathless. Then she said, “Oh, my God. It’s so…pretty.”

Her boyfriend, giving in to gentle pressure, put on the glasses, and tilted his gaze skyward.

“Yeah,” he admitted. “That is cool.”

—C. Ralph Adler

*A warm thank you to Coe Brown teacher Jill Forward for helping with this article and the media releases. Thank you to Scott Goelzer and the rest of the faculty and administrators of Coe Brown Northwood Academy for welcoming the Leitzel Center NH GLOBE Partnership to your campus.*

The GLOBE Program is an international science education initiative funded by NASA and supported by The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of State.

type: globe-news

News origin: Leitzel Center at the University of New Hampshire