By Dr. Charles Kironji Gatebe, NASA Scientist for GLOBE Student Research Campaign on Climate

I am going to take you on a research expedition to Mount Kenya, where we will hike from a base camp known as Met Station at 3050 m above mean sea level (MSL) on the southwestern slopes of the mountain and wind up at a site known as the Rangers Post at 4220 m MSL. The trek up the mountain is a long one, with far too much to observe and talk about in one blog. Therefore, I plan to break the blog into a three-part series. Part 1 will describe the location of Mt. Kenya and give some background information on the science we will do on the mountain. Part 2 will cover the journey from the Met to Rangers Point and describe the various vegetation zones. Finally, Part 3 will describe how we monitor pollution on the mountain and why this is important.

If you really like geography, you should find these blogs very interesting. And if you haven’t given it much thought, then you might begin to see why the study of geography helps us better understand the places we live in, why they matter, and how they are connected.

In a future blog, I will describe my experiences on Mt Kenya and how they shaped my scientific career.

Part 1

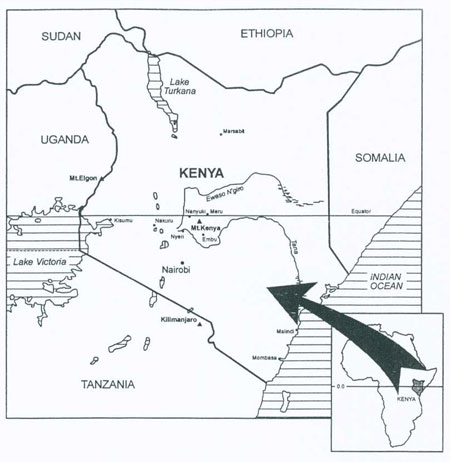

Mt. Kenya is the second highest mountain in Africa (highest point is about 5200 m MSL as compared to Kilimanjaro’s highest point at 5800 m MSL) and located on the equator (the line that divides the Earth into two equal parts: Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere). Both Mt. Kenya and Mt. Kilimanjaro have snow and glaciers on their summit. The locations of these great African mountains are shown in Figure 1. On this map, you can also see other important features, such as Lake Victoria to the west, Africa’s largest lake (68,800 Km2) and also the largest tropical lake in the world. The longest branch of the River Nile, the White Nile, has its source in Lake Victoria. The lake’s shallowness (maximum depth is about 84 m and mean depth is about 40 m), limited river inflow and large surface area relative to its volume makes it vulnerable to climate changes. To the east, you can see the Indian Ocean, which is the third largest component of the global ocean, after the Pacific Ocean (the largest) and the Atlantic Ocean (the second largest). Lake Turkana in northern Kenya, and a chain of lakes stretching southwards, are located in the basin of the Great Rift Valley that runs from northern Syria in Southwest Asia to central Mozambique in East Africa, approximately 6000 km long. We should note in passing that if the present climate in the region continues to warm, the lake levels could become lower and could severely impact economic activities such as fishing, navigation, water usage and hydropower.

Figure 1: Map of Kenya and surrounding areas showing location of Mts. Kenya (in Kenya), Kilimanjaro (in Tanzania) and Elgon (in Uganda). Water bodies such as Lake Victoria, the largest tropical lake in the world and source of the White Nile, and Indian Ocean are all shaded. The small lakes spreading from northern Kenya (Lake Turkana) through central Kenya to Tanzania are located in the basin of the Great Rift Valley, which stretches from Syria to central Mozambique.

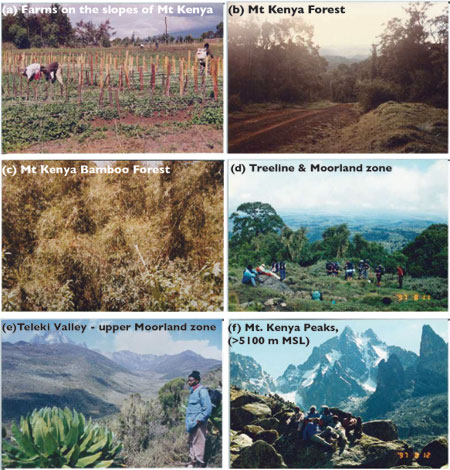

We will discover in Part 2 of this blog that mountain climates, like temperature, vary with altitude. For example, the vast gentle lower slopes of Mt. Kenya are used for farming activities as shown in Figure 2a, which then transitions to mountain forests and bamboo jungles (Figs. 2b & 2c); the alpine zone with its distinctive giant vegetation (Figs. 2d & 2e); and the rocky peak area (Fig. 2f), which is an eroded volcanic plug with its mantle of glaciers and snowfields. Currently, there is not much snow left on the mountain and the eleven remaining ice glaciers are melting at an alarming rate. If this melting trend continues they are expected to melt completely in a few decades. There are several rivers that begin on this mountain, including the Tana river, the longest river in Kenya (708 km long), and the Ewaso Ngiro (both shown in Figure 1). Both rivers would vanish with the disappearance of the Mt. Kenya glaciers. Since there are so many people whose lives depend on these rivers for their livelihood, the disappearance of these rivers could have ripple effects such as widespread migration of people and animals in search of drinking water. In fact, the situation could be more complicated, considering that there are only a few remaining catchment areas or water towers that provide the Kenyan people with a livelihood, combined with the fact that Kenya does not have enough resources to support thousands of environmental refugees. These are just a few of the potential impacts of global warming, which could be experienced not only in Kenya, but worldwide where conditions are similar. In your free time, try to identify other mountains whose glaciers are melting away. You can find more information about melting glaciers in the National Geographic News webpage.

Figure 2: Mt. Kenya showing different ecosystem zones from agricultural farms on the lower slopes to the rocky peaks. Pictures taken between July and August 1997. That’s me in the lower left photo!

wow. looks like a life time adventure.

thanks for sharing.